There was big news in the bond market this month: China has finally relented to international pressure and revalued its currency. After over a decade of being pegged at a fixed rate to the dollar, the Chinese yuan was allowed to appreciate by 2.1% and will be pegged to an unspecified basket of currencies rather than to the dollar itself.

As I’ve discussed recently, Asian central banks have been purchasing huge quantities of US bonds in order to weaken their own currencies against the dollar. These bond purchases have resulted in lower yields than would have occurred otherwise (due both to the increased demand for bonds and to the inflation-taming effect of the artificially strengthened dollar). The prime mover in this “dollar-recycling” dynamic has been China, whose fixed peg to the dollar has forced the other Asian countries to weaken their currencies in order to stay competitive. Thus, people have looked to China to make the first move in ending the Asian’s US dollar-recycling scheme.

So China has finally made a move, if only a small one. The 2.1% yuan revaluation is pretty insignificant considering the magnitude of our trade deficit with China, and the indeterminate nature of the currency basket makes it tough to determine an effect. It is likely that in the very short-term, China’s currency repeg will not have a big effect.

Nonetheless, China has made a move of great long-term import. The decade-old fiscal “dance of death”—whereby the Asians lend us ever more money and we send that money right back in exchange for ever more consumer goods, only to borrow more—is finally drawing to a close. It may take a while to play out, but the endgame has begun.

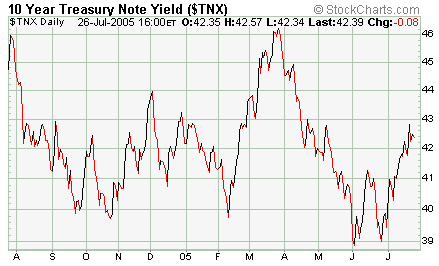

Long-Term Rates

Long rates have risen pretty steadily since last month’s report, but they remain well under the March highs for the time being:

The yuan revaluation announcement gave the bond market a brief scare, but things have calmed down in the days thereafter. It remains to be seen how long the current uptrend in rates will last, but for now long rates remain pretty friendly to the housing market.

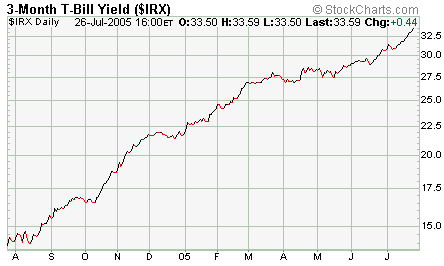

Short-Term Rates

Short rates have marched steadily upwards on increasing expectations of Fed tightening:

As of last month, I opined that the Fed was unlikely to raise rates a whole lot more because the yield curve was dangerously close to inverting and the ISM Purchasing Managers Index was indicating an imminent shrinking of manufacturing sector activity.

Since that time, things have changed to give the Fed a little more elbow room. The past month’s rise in long-term rates means that the Fed can tighten that much more before inverting the yield curve. And the ISM survey experienced a nice bounce, as well, halting its multi-month decline:

While other leading indicators still point to an economic slowdown, the Fed took the added wiggle room as a sign to talk up the economy and to talk tough on interest rates. Of course, talk is one of the Fed’s main policy tools. Simply implying future interest rate increases is enough to reign in lending in some cases, so whether Greenspan follows through with the rate increases or not is an open question. The markets are currently pricing in a further 75 basis points of rate hikes (from today’s 3.25% to 4%) by the end of the year. I’m not so sure we will get to 4%, but we’ll know soon enough.

Conclusion

Both long and short rates have risen, but neither by enough to soften the housing market. As it stands, it does not appear that rates will put much downward pressure until either they rise significantly more or a lot of ARMs start resetting. The latter isn’t set to start happening just yet, as far as I can tell, and as for the former we will just have to keep a close eye on the market to look for the effects of Asian currency revaluation, Fed tightening, and anything else that comes along to shake up the bond market. Until then, housing shouldn’t come under any pressure from this front.

Treasury yield charts courtesy of StockCharts.com.